In the ongoing hysteria surrounding all things SDN, one important thing gets often overlooked. You don’t build SDN for its own sake. SDN is just a little cog in a big machine called “cloud”. To take it even further, I would argue that the best SDN solution is the one that you don’t know even exists. Despite what the big vendors tell you, operators are not supposed to interact with SDN interface, be it GUI or CLI. If you dig up some of the earliest presentation about Cisco ACI, when the people talking about it were the actual people who designed the product, you’ll notice one common motif being repeated over and over again. That is that ACI was never designed for direct human interaction, but rather was supposed to be configured by a higher level orchestrating system. In data center environments such orchestrating system may glue together services of virtualization layer and SDN layer to provide a seamless “cloud” experience to the end users. The focus of this post will be one incarnation of such orchestration system, specific to SP/Telco world, commonly known as NFV MANO.

NFV MANO for Telco SDN

At the early dawn of SDN/NFV era a lot of people got very excited by “the promise” and started applying the disaggregation and virtualization paradigms to all areas of networking. For Telcos that meant virtualizing network functions that built the service core of their networks - EPC, IMS, RAN. Traditionally those network functions were a collection of vertically-integrated baremetal appliances that took a long time to commission and had to be overprovisioned to cope with the peak-hour demand. Virtualizing them would have made it possible to achieve quicker time-to-market, elasticity to cope with a changing network demand and hardware/software disaggregation.

As expected however, such fundamental change has to come at price. Not only do Telcos get a new virtualization platform to manage but they also need to worry about lifecycle management and end-to-end orchestration (MANO) of VNFs. Since any such change presents an opportunity for new streams of revenue, it didn’t take long for vendors to jump on the bandwagon and start working on a new architecture designed to address those issues.

The first problem was the easiest to solve since VMware and OpenStack already existed at that stage and could be used to host VNFs with very little modifications. The management and orchestration problem, however, was only partially solved by existing orchestration solutions. There were a lot of gaps between the current operational model and the new VNF world and although these problems could have been solved by Telcos engaging themselves with the open-source community, this proved to be too big of a change for them and they’ve turned to the only thing they could trust - the standards bodies.

ETSI MANO

ETSI NFV MANO working group has set out to define a reference architecture for management and orchestration of virtualized resources in Telco data centers. The goal of NFV MANO initiative was to do a research into what’s required to manage and orchestrate VNFs, what’s currently available and identify potential gaps for other standards bodies to fill. Initial ETSI NFV Release 1 (2014) defined a base framework through relatively weak requirements and recommendations and was followed by Release 2 (2016) that made them more concrete by locking down the interfaces and data model specifications. For a very long time Release 1 was the only available NFV MANO standard, which led to a lot of inconsistencies in each vendors’ implementations of it. This was very frustrating for Telcos since it required a lot of integration effort to build a multi-vendor MANO stack. Another potential issue with ETSI MANO standard is its limited scope - a lot of critical components like OSS and EMS are left outside of it which created a lot of confusion for Telcos and resulted in other standardisation efforts addressing those gaps.

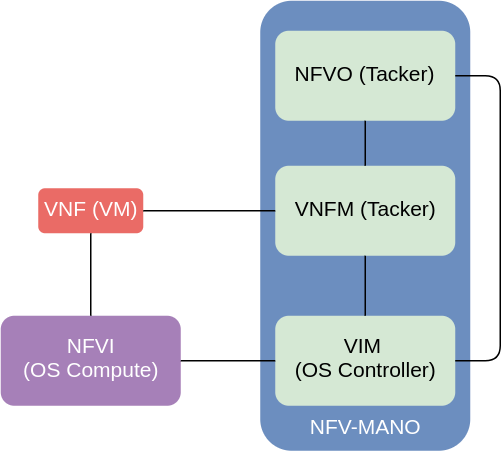

On the below diagram I have shown an adbridged version of the original ETSI MANO reference architecture diagram adapted to the use case I’ll be demonstrating in this post.

This architecture consists of the following building blocks:

- NFVI (NFV Infrastructure) - OpenStacks compute or VMware’s ESXI nodes

- VIM (Virtual Infrastructure Manager) - OpenStack’s controller/API or VMware’s vCenter nodes

- VNFM (VNF Manager) - an element responsible for lifecycle management (create,delete,scale) and monitoring of VNFs

- NFVO (NFV Orchestrator) - an element responsible for lifecyle management of Network Services (described below)

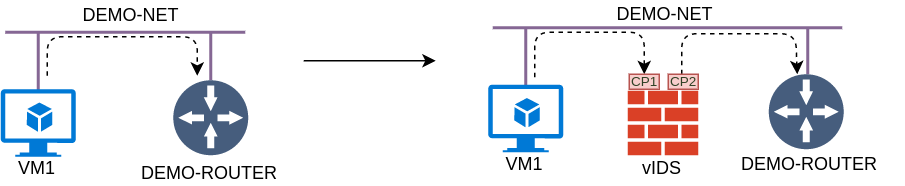

All these elements are working together towards a single goal - managing and orchestrating a Network Service (NS), which itself is comprised of multiple VNFs, Virtual Links (VLs), VNF Forwarding Graphs (VNFFGs) and Physical Network Functions (PNFs). In this post I create a NS for a simple virtual IDS use case, described in my previous SFC post. The goal is to steer all ICMP traffic coming from VM1 through a vIDS VNF which will forward the traffic to its original destination.

Before I get to the implementation, let me give a quick overview of how a Network Service is build from its constituent parts, in the context of our vIDS use case.

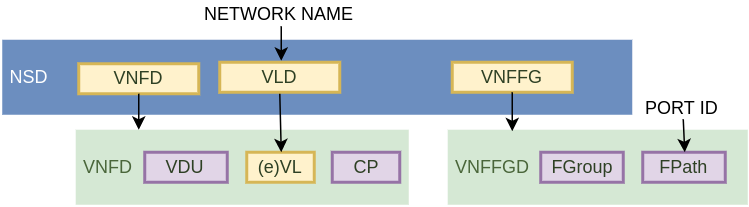

Relationship between NS, VNF and VNFFG

According to ETSI MANO, a Network Service (NS) is a subset of end-to-end service implemented by VNFs and instantiated on the NFVI. As I’ve mentioned before, some examples of a NS would be vEPC, vIMS or vCPE. NS can be described in either a YANG or a Tosca template called NS Descriptor (NSD). The main goal of a NSD is to tie together VNFs, VLs, VNFFGs and PNFs by defining relationship between various templates describing those objects (VNFDs, VLDs, VNFFGDs). Once NSD is onboarded (uploaded), it can be instantiated by NFVO, which communicates with VIM and VNFM to create the constituent components and stitch them together as described in a template. NSD normally does not contain VNFD or VNFFGD templates, but imports them through their names, which means that in order to instantiate a NSD, the corresponding VNFDs and VNFFGDs should already be onboarded.

VNF Descriptor is a template describing the compute and network parameters of a single VNF. Each VNF consists of one or more VNF components (VNFCs), represented in Tosca as Virtual Deployment Units (VDUs). A VDU is the smallest part of a VNF and can be implemented as either a container or, as it is in our case, a VM. Apart from the usual set of parameters like CPU, RAM and disk, VNFD also describes all the virtual networks required for internal communication between VNFCs, called internal VLs. VNFM can ask VIM to create those networks when the VNF is being instantiated. VNFD also contains a reference to external networks, which are supposed to be created by NFVO. Those networks are used to connect different VNFs together or to connect VNFs to PNFs and other elements outside of NFVI platform. If external VLs are defined in a VNFD, VNFM will need to source them externally, either as input parameters to VNFM or from NFVO. In fact, VNF instantiation by VNFM, as described in Tacker documentation, is only used for testing purposes and since a VNF only makes sense as a part of a Network Service, the intended way is to use a NSD to instantiate all VNFs in production environment.

The final component that we’re going to use is VNF Forwarding Graph. VNFFG Descriptor is an optional component that describes how different VNFs are supposed to be chained together to form a Network Service. In the absence of VNFFG, VNFs will fall back to the default destination-based forwarding, when the IPs of VNFs forming a NS are either automatically discovered (e.g. through DNS) or provisioned statically. Tacker’s implementation of VNFFG is not fully integrated with NSD yet and VNFFGD has to be instantiated separately and, as will be shown below, linked to an already running instance of a Network Service through its ID.

Using Tacker to orchestrate a Network Service

Tacker is an OpenStack project implementing a generic VNFM and NFVO. At the input it consumes Tosca-based templates, converts them to Heat templates which are then used to spin up VMs on OpenStack. This diagram from Brocade, the biggest Tacker contributor (at least until its acquisition), is the best overview of internal Tacker architecture.

For this demo environment I’ll keep using my OpenStack Kolla lab environment described in my previous post.

Step 1 - VIM registration

Before we can start using Tacker, it needs to know how to reach the OpenStack environment, so the first step in the workflow is OpenStack or VIM registration. We need to provide the address of the keystone endpoint along with the admin credentials to give Tacker enough rights to create and delete VMs and SFC objects:

cat << EOF > ./vim.yaml

auth_url: 'http://192.168.133.254:35357/v3'

username: 'admin'

password: 'admin'

project_name: 'admin'

project_domain_name: 'Default'

user_domain_name: 'Default'

EOF

tacker vim-register --is-default --config-file vim.yaml --description MYVIM KOLLA-OPENSTACK

The successful result can be checked with tacker vim-list which should report that registered VIM is now reachable.

Step 2 - Onboarding a VNFD

VNFD defines a set of VMs (VNFCs), network ports (CPs) and networks (VLs) and their relationship. In our case we have a single cirros-based VM with a pair of ingress/egress ports. In this template we also define a special node type tosca.nodes.nfv.vIDS which will be used by NSD to pass the required parameters for ingress and egress VLs. These parameters are going to be used by VNFD to attach network ports (CPs) to virtual networks (VLs) as defined in the substitution_mappings section.

cat << EOF > ./vnfd.yaml

tosca_definitions_version: tosca_simple_profile_for_nfv_1_0_0

description = Cirros vIDS example

node_types:

tosca.nodes.nfv.vIDS:

requirements:

- INGRESS_VL:

type: tosca.nodes.nfv.VL

required: true

- EGRESS_VL:

type: tosca.nodes.nfv.VL

required: true

topology_template:

substitution_mappings:

node_type: tosca.nodes.nfv.vIDS

requirements:

INGRESS_VL: [CP1, virtualLink]

EGRESS_VL: [CP2, virtualLink]

node_templates:

VDU1:

type: tosca.nodes.nfv.VDU.Tacker

properties:

availability_zone: nova

flavor: m1.nano

image: cirros

mgmt_driver: noop

user_data_format: RAW

user_data: |

#!/bin/sh

sudo cirros-dhcpc up eth1

sudo ip rule add iif eth0 table default

sudo ip route add default via 10.0.0.1 dev eth1 table default

sudo sysctl -w net.ipv4.ip_forward=1

CP1:

type: tosca.nodes.nfv.CP.Tacker

properties:

anti_spoofing_protection: false

requirements:

- virtualBinding:

node: VDU1

CP2:

type: tosca.nodes.nfv.CP.Tacker

properties:

anti_spoofing_protection: false

requirements:

- virtualBinding:

node: VDU1

EOF

tacker vnfd-create --vnfd-file vnfd.yaml vIDS-TEMPLATE

Step 4 - Onboarding a NSD

In our use case the NSD template is going to really small. All what we need to define is a single VNF of the tosca.nodes.nfv.vIDS type that was defined previously in the VNFD. We also define a VL node which points to the pre-existing demo-net virtual network and pass this VL to both INGRESS_VL and EGRESS_VL parameters of the VNFD.

cat << EOF > ./nsd.yaml

tosca_definitions_version: tosca_simple_profile_for_nfv_1_0_0

imports:

- vIDS-TEMPLATE

topology_template:

node_templates:

vIDS:

type: tosca.nodes.nfv.vIDS

requirements:

- INGRESS_VL: VL1

- EGRESS_VL: VL1

VL1:

type: tosca.nodes.nfv.VL

properties:

network_name: demo-net

vendor: tacker

EOF

tacker nsd-create --nsd-file nsd.yaml NSD-vIDS-TEMPLATE

Step 5 - Instantiating a NSD

As I’ve mentioned before, VNFFG is not integrated with NSD yet, so we’ll add it later. For now, we have provided enough information to instantiate our NSD.

tacker ns-create --nsd-name NSD-vIDS-TEMPLATE NS-vIDS-1

This last command creates a cirros-based VM with two interfaces and connects them to demo-net virtual network. All ICMP traffic from VM1 still goes directly to its default gateway so the last thing we need to do is create a VNFFG.

Step 6 - Onboarding and Instantiating a VNFFG

VNFFG consists of two two types of nodes. The first type defines a Forwarding Path (FP) as a set of virtual ports (CPs) and a flow classifier to build an equivalent service function chain inside the VIM. The second type groups multiple forwarding paths to build a complex service chain graphs, however only one FP is supported by Tacker at the time of writing.

The following template demonstrates another important feature - template parametrization. Instead of defining all parameters statically in a template, they can be provided as inputs during instantiation, which allows to keep templates generic. In this case I’ve replaced the network port id parameter with PORT_ID variable which will be provided during VNFFGD instantiation.

cat << EOF > ./vnffg.yaml

tosca_definitions_version: tosca_simple_profile_for_nfv_1_0_0

description = vIDS VNFFG tosca

topology_template:

inputs:

PORT_ID:

type: string

description = Port ID of the target VM

node_templates:

Forwarding_Path-1:

type: tosca.nodes.nfv.FP.Tacker

description = creates path (CP1->CP2)

properties:

id: 51

policy:

type: ACL

criteria:

- network_src_port_id: { get_input: PORT_ID }

- ip_proto: 1

path:

- forwarder: vIDS-TEMPLATE

capability: CP1

- forwarder: vIDS-TEMPLATE

capability: CP2

groups:

VNFFG1:

type: tosca.groups.nfv.VNFFG

description = Set of Forwarding Paths

properties:

vendor: tacker

version: 1.0

number_of_endpoints: 1

dependent_virtual_link: [VL1]

connection_point: [CP1]

constituent_vnfs: [vIDS-TEMPLATE]

members: [Forwarding_Path-1]

EOF

tacker vnffgd-create --vnffgd-file vnffgd.yaml VNFFG-TEMPLATE

Note that the VNFFGD has been updated to support multiple flow classifiers which means you many need to update the above template as per the sample VNFFGD template

In order to instantiate a VNFFGD we need to provide two runtime parameters:

- OpenStack port ID of VM1 for forwarding path flow classifier

- ID of the VNF created by the Network Service

All these parameters can be obtained using the CLI commands as shown below:

CLIENT_IP=$(openstack server list | grep VM1 | grep -Eo '[0-9]+\.[0-9]+\.[0-9]+\.[0-9]+')

PORT_ID=$(openstack port list | grep $CLIENT_IP | awk '{print $2}')

echo "PORT_ID: $PORT_ID" > params-vnffg.yaml

vIDS_ID=$(tacker ns-show NS-vIDS-1 -f value -c vnf_ids | sed "s/'/\"/g" | jq '.vIDS' | sed "s/\"//g")

The following command creates a VNFFG and an equivalent SFC to steer all ICMP traffic from VM1 through vIDS VNF. The result can be verified using Skydive following the procedure described in my previous post.

tacker vnffg-create --vnffgd-name VNFFG-TEMPLATE \

--vnf-mapping vIDS-TEMPLATE:$vIDS_ID \

--param-file params-vnffg.yaml VNFFG-1

Other Tacker features

This post only scratches the surface of what’s available in Tacker with a lot of other salient features left out of scope, including:

- VNF monitoring - through monitoring driver its possible to do VNF monitoring from VNFM using various methods ranging from a single ICMP/HTTP ping to Alarm-based monitoring using OpenStack’s Telemetry framework

- Enhanced Placement Awareness - VNFD Tosca template extensions that allow the definition of required performance features like NUMA topology mapping, SR-IOV and CPU pinning.

- Mistral workflows - ability to drive Tacker workflows through Mistral

Conclusion

Tacker is one of many NFV orchestration platforms in a very competitive environment. Other open-source initiatives have been created in response to the shortcomings of the original ETSI Release 1 reference architecture. The fact the some of the biggest Telcos have finally realised that the only way to achieve the goal of NFV orchestration is to get involved with open-source and do it themselves, may be a good sign for the industry and maybe not so good for the ETSI NFV MANO working group. Whether ONAP with its broader scope becomes a new de-facto standard for NFV orchestration, still remains to be seen, until then ETSI MANO remains the only viable standard for NFV lifecycle management and orchestration.